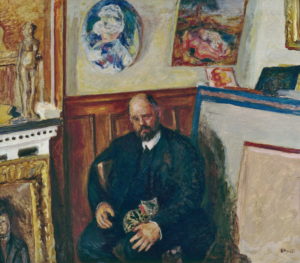

R835 – Portrait du peintre Alfred Hauge, 1899 (FWN532)

Pavel Machotka

(Cliquer sur l’image pour l’agrandir)

Avec le buste d’Alfred Hauge, Cézanne a commencé à peindre des portraits dans un nouveau style, moins détaillé et apparemment plus plat, avec des contours marqués et des taches plus grandes et plus détachées ; mais le changement de style était une question de choix, il n’était pas inévitable ; la Jeune Italienne accoudée et La Dame au livre, réalisés plus tard (respectivement en 1900 et 1902-1904) sont tellement intégrés que les taches s’y confondent avec l’ensemble. mais les taches dans le portrait d’Alfred Hauge semblent mécaniques – davantage visibles et plus abstraites- et le portrait demeure plus raide. Le modèle, 23 ans à l’époque, était un jeune peintre danois ; sa photographie montre un homme aux yeux très écartés avec une abondante tignasse[1], et son portrait le montre en un jeune homme correct, soigneusement habillé, collet monté.

Il a passé au moins assez de temps avec Cézanne pour être accueilli chez le peintre et que celui-ci fasse son portrait, mais en dehors de cela, nous ne connaissons rien de lui ; dans sa lettre à un ami juste après la visite, il était aussi critique de Cézanne qu’il était admiratif, et il se peut que le peintre se soit aperçu de quelque chose d’ambivalent dans son attitude. C’est peut-être le travail du pinceau dans le manteau et le fond qui trahit l’attitude de Cézanne : les touches bougent avec rigidité dans une seule direction, et bien que ceci ait son utilité formelle – en projetant le corps en avant –, le tableau semble mécanique et sans caractère. Les contours du manteau ont la vigueur de ceux du Portrait de M. Ambroise Vollard, cependant, et le jeu de couleur est presque aussi économe : un sienne brûlé contre un bleu-noir. Cette combinaison simple se retrouve également dans le visage, avec pour résultat de le faire paraître aussi exsangue qu’artistique ; la bouche, en revanche, sensuelle au départ, est délimitée en des touches marrons très énigmatiques.

________

With the head-and-shoulders painting of Alfred Hauge, Cézanne’s portraits could become abstract, rougher and seemingly flatter, with emphatic outlines and larger and more detached patches. Whether they did so or not was a matter of choice, not inevitability; the Jeune Italienne accoudée and La Dame au livre, done later (1900 and 1902-04 respectively), are so well integrated that their patches merge with the whole. But the patches in the portrait of Hauge seem mechanical – more visible and abstract – and the portrait remains stiff. The sitter, 23 at the time, was a young Danish painter; his photograph shows a man with large eyes set far apart and an abundant head of hair[2], and this portrait shows him to be a very correct, carefully dressed, prim young man. He spent at least enough time with Cézanne to be hosted and have his portrait painted, but beyond that we know nothing about him; in his letter to a friend right after the visit, he was as critical of Cézanne as he was admiring, and something of his ambivalent attitude may have become apparent to the painter. It is perhaps the brushwork in the coat and background that betrays Cézanne’s attitude: the touches move rigidly in one direction only, and while this has its formal use—it thrusts the body forward—it seems mechanical and listless. The outlines of the coat have the vigor of those in the Portrait de M. Ambroise Vollard, however, and the color scheme is almost as spare: a burnt siena against a blue-black. This simple scheme carries into the face as well, with the result that he seems as bloodless as he should be artistic; the mouth, on the other hand, sensuous to begin with, is outlined in very puzzling brown touches.

[1] Voir sa photographie et le texte de sa lettre à un ami décrivant sa rencontre avec Cézanne dans Rewald, PPC, vol. 1, p. 500.

[2] See his photograph and the text of his letter to a friend describing his meeting with Cézanne, in Rewald, PPC, vol. 1, p. 500.

Source: Machotka, Cézanne: the Eye and the Mind.

Noter la présence de ce portrait en bas à gauche du portrait de Vollard par Bonnard :