Cézanne’s portraits: The human face of masterly painting

University of California, Santa Cruz

(Published in the catalog of the exhibition Cézanne, Milano, Italiy, 2012)

The art dealer Vollard tells us that when Cézanne painted his portrait, he sat him on a chair perched on top of a crate and instructed him to keep his balance and not move – and goes on to say that when he nodded off and fell down with the chair, Cézanne exclaimed, “You wretch! … Do I have to tell you again you must sit like an apple? Does an apple move?”[1] The image of the immobile apple is evocative, but it must not be overinterpreted: it does not mean, as has been thought, that for Cézanne the portrait head was nothing more than a still life, a mere occasion to study volumes, an object emotionally distant from the painter. Such distance is not generally assumed in the work of other portraitists, for whom stillness in sitters is a matter of necessity.

And so it was in fact with Cézanne: on the basis of the visual evidence of the portraits, his exceptional concentration on the work at hand did not exclude or suppress an emotional relationship with his models. The portraits suggest, for example, an attitude of respect (for his art dealer Vollard and the critic Geffroy, in Portrait de M. Ambroise Vollard, (FWN531-R811),

and Portrait de Gustave Geffroy, Fig. 1), a sense of camaraderie (with his boyhood friend, in Portrait de Henri Gasquet, Fig. 2), a feeling of tenderness (for his young son, in Portrait du fils de l’artiste, Fig. 5), an unconscious identification (with the old gardener, in Le jardinier Vallier, Fig. 11), a vague mistrust (of the young Danish painter, in Portrait d’Alfred Hauge, fig.10), or a shifting ambivalence of feeling (toward his wife Hortense, which ran from utter tenderness, in Madame Cézanne dans la serre, Fig. 9, to near indifference, in Portrait de Madame Cézanne (FWN489-R650).

The presence of a relationship must be noted if we are to respond to the portraits both as masterly paintings and as human documents.

Cézanne’s portraits therefore have a special place in his oeuvre, as much for the observer who studies them as for the painter who had painted them. As observers, in looking at a portrait, we recognize the individuality of the sitter — easily distinguishing one sitter one from another — and sense the quality of Cézanne’s relationship: a palpable closeness or distance, a small-scale involvement or a large-scale one, a formality or informality of conception. Naturally, as with other genres of Cézanne’s painting, we are moved by the painter’s technical mastery, his juxtaposition of the colors, and his deep integration of the surface through a consistent touch, and these form an indissoluble whole in our response to the painting. With landscapes and still lives, on the other hand, our response to the subject is less intense, more uniform: in landscapes it is the handling of the shapes and their relationships that leaps to the eye, and in still lives it is, in addition, the fine equilibrium of the colors and the complex, thoughtful, juxtaposition of the simple forms. No genre in Cézanne’s oeuvre claims greater artistic achievements or more masterpieces than any other; each simply reflects different balances of Cézanne’s intentions and predispositions.

From our response to the portraits we presume that in painting them, the painter himself was moved by his response to the sitter and we tend to note, justifiably I think, that the form of the painting reflects that respose at least in part. Naturally, the form reflects the level of his stylistic development as well, but not in any automatic way: Cézanne was not constrained by it. At times, as in Madame Cézanne à la jupe rayée of 1877 (Fig. 4), he allowed the style to prevail over the subject, while at other times he allowed the subject to prevail or to push the style in new directions, as in Portrait de l’artiste au fond rose of about 1875 (FWN436-R274).

The important matter to note is that the portrait is a complex outcome of aesthetic purposes, technical decisions — as well as emotional responses.

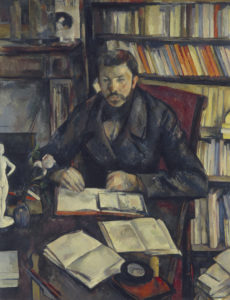

The Portrait de Gustave Geffroy of 1895-96 (Fig. 1, FWN516-R791), for example, is a complex resolution of several intentions.

Fig. 1. Portrait of Gustave Geoffrey FWN516-R791

Oil on canvas

1895

116 x 89 cm.

We can certainly discern ambition: to paint a complex painting that shows the sitter in the context of his cluttered study (with his desk arranged, one would assume, to achieve a satisfactory composition); to achieve a likeness (whose success we can judge from a contemporary photograph of Geffroy); and to create a work of art that masterfully resolves a series of pictorial tensions. The portrait also suggests Cézanne’s attitude of respect for the critic‘s important position, and conveys a psychological distance that allows, and perhaps even invites, the impressive, large-scale composition. In a photograph we see Geffroy as a slight man with sloping shoulders and a smooth, oval head, and this is essentially the figure that is revealed in the painting. But if the painting is obviously a portrait, it is also a formal composition which, for the sake of clear resonances between the forms, simplifies some of the accidents of nature. The head and the hairline, for example, are smooth, the eyes betray no specific expression, and the hands, altogether schematic, do not tell us whether their possessor is strong or weak, whether at times they write and at other times caress.

Yet the picture is magnificent, even more so when seen in the original, in full size and well illuminated. Something about it is grave and fully realized, and it is more than just the sitter’s monumental dignity; that can be seen in black and white reproductions, too, but without color the picture fails to come to life. It is color that fully realizes the painter’s intentions. It pivots around an opposition of the complementary colors blue-black and orange, and includes a mediating third element, a cool burgundy. Complementaries balance naturally, but the third element, here the burgundy, is crucial; located on the cool side of red, it forms a color bridge between them, just as the chair back makes a physical link between the figure and the book case.

Color also guides our grasp of the composition. Our eyes are made to move between the orange of the books near the sitter’s head and the orange edging on the flat book in front of him; in this way we have to look down at the books, realize that they lead us back toward the sitter and, in their zigzag, echo the slopes of the sitter’s upper arms; they underscore the pyramid that culminates in the face. The row of orange books at the sitter’s head also ensures that we return to the head. Their vivid orange color admittedly competes for attention, but this is in fact an advantage: the orange hue pulls us to the right of the head, balancing the leftward gaze, and the nearness of the books to the head reminds us subtly that the sitter lives as much in his intellect as he does in his body.

In this portrait, then, Cézanne has set himself a high goal — to unite the appearance of the sitter with the context in which he works and incorporate them in a complex, carefully resolved composition. The ambitious goal also revealed a respectful distance from the sitter, which may have encouraged, and certainly allowed, the monumental treatment. We respond in two ways: at times to the complexity of the forms, at other times to the sitter and the work he does. Looking at form, we may come to feel one more pleasure, the painting‘s central triumph: the face. The face contains all the colors of the painting: blue-greys for the shadows and the eyes, and pale yellows, oranges, even spots of burgundy in the skin. When we return to it, we are once again looking at a portrait.

A quite different portrait painted within a year or so of the Geffroy painting (1896) reveals neither formality, nor monumentality, nor complexity: it was done of Henri Gasquet, Cézanne’s former schoolmate (Fig. 2, FWN522-R810).

Fig. 2. Portrait d’Henri Gasquet FWN522-R810

Oil on canvas

1896

56 x 47 cm

While Cézanne’s intentions seem more modest – the subject was a baker and Cézanne’s boyhood friend — it is itself a brilliant achievement, but in a more straightforward manner. Gasquet appears as a physical and psychological being; as Rewald puts it[2], he had grown prosperous, had a dignified face and grave manner, and looked like a small-town notary. (Cézanne was also friends with his son Joachim, a poet, with whom he conversed at length about art, but that relationship had its share of tensions – which are reflected in the unfinished portrait, Portrait de Joachim Gasquet (FWN521–R809).

Here no such tensions are evident; Henri seems very present, dominating the composition by his contented air, inclined head, rakishly tilted hat, and unlit cigar. However formally one usually views paintings, here it is impossible not to take pleasure in Gasquet’s self-assurance, and not to enjoy what I take to be Cézanne’s own self-confidence, expressed in his straight, definitive, uncorrected touches. And yet the formal pleasures are considerable as well: the hat brim, the cigar, the shoulder, one of the lapels, all make for one simple movement, while the other shoulder and lapel, and the cut of the coat, create a natural counterbalance. Since the the head leans strongly to the left, Cézanne adds a counterweight – he contains the head subtly in a rectangle that leans to the right. The color harmony is much simpler here than in the Geffroy, but it is equally balanced and complete: the blue-blacks of the hat and coat are set against the ruddy, tanned face, with the grey-greens of the background outlining the features of the face and providing the needed modeling. None of the balanced forms or colors seem forced; on the contrary, the simple equilibrium of the painting seems a natural expression of the man’s dignity.

Much earlier in his career (in 1866) and then on occasion later (among others, in 1877) Cézanne painted several portraits in which his painting style dominated his subject. Both years were, admittedly, periods of intense concentration on the unity of his painting surface; the first period witnessed the so-called couillard style, with impetuous strokes of the palette knife building up a bravura, alla prima surface, while the second period, more variable in actual touches of the brush, was notable by its scrupulous attention to consistency of surface. The paintings done in that year remain portraits, in the sense that the sitters are perfectly recognizable, but as we study them, we cannot but respond first and foremost to the primacy of their style. We may suspect that it was Cézanne’s ease in their company that allowed the style to dominate the likeness.

The first period produced an exceptional series of ten portraits of the same man, Cézanne’s maternal uncle Dominique. Presumably a good-natured, patient man, he let himself be dressed in various disguises, playing monk, judge or sportsman, and it is these variations of disguise, as well as differences in the pictures’ formats, that forestall repetition. Cézanne’s handling of the palette knife in all of them is self-assured. He forms eyebrows, eyes, nose, beard, hands, and tunic, and models the face and hair with well-placed dabs for the highlights and shadows. In L’Homme au bonnet de coton (Fig. 3, FWN412-R107)), one of the two largest pictures in the series, Cézanne works with the same bravura impasto as in the others, and achieves a monumental simplicity with his simple composition and straightforward color scheme.

Fig. 3. L’homme au bonnet de coton (l’oncle Dominique) FWN412-R107

Oil on canvas

ca 1866

79.7 x 64.1 cm)

With a black and white color foundation, and a neutral grey ground, he sets a red cravatte against a complementary green bonnet; he then lets the left inclination of the bonnet balance the rightward sweep of the white coat. These choices seem as quick and intuitive as does the choice of grey for the background, which makes the fairly dark skin appear luminous.

Starting directly with the knife and painting wet-on-wet meant a kind of commitment to reaching a point of no return; there could be no corrections and style would risk overwhelming the likeness. It was a risk Cézanne was evidently ready to take for the sake of the bravura touch. Style could, in any case, dominate the painting equally forcefully when the touch was thoughtful, slow, and physically thin, as in the paintings of the year 1877. The work of that year reveals a new development, the use of blockish touches to build up a highly rhythmical, integrated painting – and this innovation seems so significant in Cézanne’s development that one can understand perfectly if he wished to apply it to portraits even at the risk of compromising the likeness.

In portraits, the most successful, even arresting, use of this touch is seen in the portrait of his wife, Madame Cézanne à la jupe rayée (Fig. 4, FWN443-R324).

Surely requiring patient sittings and Madame Cézanne’s prior acceptance of whatever the result of Cézanne’s stylistic innovating might be, the painting is a masterpiece. It is solidly constructed on the firm foundation of Mme Cézanne’s voluminous, vertically striped skirt, and, although her body tapers toward the top, the composition opens out again with the massive, brillant, red chair at the sitter’s back. With the figure resting against one arm of the chair, Cézanne distends the back of the chair on the other side, to balance her; so successful is the internal balance that this swelling is barely noticeable.

One does have to remind oneself that the painting is a portrait, so dominant are the painter’s devices. The armchair is a frank crimson, but it is placed in the calm company of the mustard wallpaper behind it; even the blues of the jacket, which range from violet to green, rival and placate the red chair. The painting is a tour de force of color use, surface integration, and compositional spareness, and while the head tells us that its subject is Madame Cézanne, it is more a masterly picture than a likeness.

Cézanne’s relation to the human head is once again different when we come to the tender regard he has for his son’s appearance and the unsparingly analytic attitude he adopts toward his own face. His love toward his son protects not only the appearance, but also allows a rare measure of expression in the face, appropriately childlike; his interest in his own face, on the other hand, at least after a few early histrionic self-portraits from the years 1862-66, is as a vehicle for close stylistic scrutiny. In neither case does the style overwhelm the likeness; in the one case Cézanne’s hand is guided by affection, in the other it is propelled by the need to analyze.

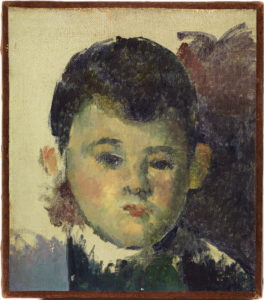

The intimate little study, Portrait du fils de l’artiste (Fig. 5, FWN456-R464), is a particularly touching example of the former, and is the more striking as it was done at about the same time as Madame Cézanne à la jupe rayée.

The paintings contrast sharply: while the mother provides what seems to be a mere instrument for a powerful stylistic analysis, the little boy is seen as himself, with his head all oval lines, gentle convexities, and smooth, nearly translucent skin tones; it is a loving homage to that wished-for quality, a child’s innocence. Cézanne is incapable, of course, of at least a minimum of self-discipline in the treatment and does attend carefully to a harmonious modeling of the head with colors ranging from pink-reds to blue-greens; he also underscores his regard for the boy’s appearance by laying the touches on the canvas gently. But as fine an example as this is of Cézanne’s hand, it remains above all a delicate portrait.

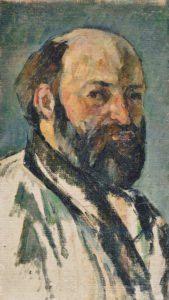

A quite different attitude toward the head is revealed in a very small self-portrait, only a bit taller than the portrait of his son, which was painted perhaps two years later (Fig. 6, FWN444-R385).

It would be called a sketch were it not painted with an evident confidence, self-sufficiency, and finality. Cézanne turns his head to illuminate only half his face, creating a sharp, dividing shadow that emphasizes the structure of his head rather than his expression (although the expression is self-assured enough). With no trace of the drama of the earliest self-portraits, the painting shows him straightforwardly, as a man studying his face in the mirror, and presents him at a robust age as the simple homme du midi that he was. It is direct and self-assured in handling, relying on quick slashes of the brush to create the volumes of the torso and slower, shorter ones in grey-greens and flesh tones to balance the colors, model the head, and depict the grey hairs in his beard—a model of efficacy that loses nothing in sensuousness.

These short touches are examples of a style that dominated Cézanne’s work during the years 1880-1885; this style, the “parallel touch” was a compelling invention[3], one that analyzed form into its component planes, recreated its volumes and colors on the canvas, and closely unified his compositions. Cézanne found it useful in still lives, landscapes and narrative paintings equally. In portraits, however, he used it more sparingly, softening its edges when painting the portraits of others — but leaving a very incisive form of it to images of himself. He left no documents to explain his practice, but we may make an informed guess from the evidence: since the touch was relentlessly analytic and unsparing, if it were to subject a head to rigorous study, the best head for the purpose would be his own.

In the analytical self-portraits from this period the parallel touch, although used as the dominant instrument for depicting the likeness, nevertheless stops short of overwhelming it. Instead, the touch becomes part of a grander design, one that is as much an abstract composition as it is a likeness. In Portrait de l’artiste au papier peint olivâtre (Fig. 7, FWN462-R482), painted about a year later, it is not the touch itself that strikes one, but the central position of the head, with much empty space above, which seemingly give the painter a very short stature.

Fig. 7. Portrait de l’artiste au papier peint olivâtre FWN462-R482

Oil on canvas

1880-1881

33.6 x 26 cm

Roger Fry, a most sensitive observer, thought that the artist’s figure was quite diminished: he wrote that « Cézanne has descended from the fiery theatrical self-interpretation of his youth to this shrunken and timid middle-aged man »[4]. It is not the painter‘s appearance that is in question here, however – Cézanne will soon again paint himself as self-possessed and strong – but Cézanne’s aesthetic purpose. If we look instead at the peculiar shape of the head — more pointed than in any other self-portrait – then we see that it is clearly meant to be embedded in the framework of diagonals created by the criss-crossing diamonds of the wallpaper; pointed, the head fits the pattern closely. Now the lapels of the coat become part of the pattern as well, as do the eyebrows, eyelids, and beard, which themselves are more angular than usual. Even Cézanne’s ear loses it normal inner curves and becomes a simple diamond.

Cézanne’s own head – a portrait, admittedly, but one that takes liberties with the shapes — has here become the focus of the painter’s study of pictorial composition, where perhaps no one else’s head would have served. The picture is, nervertheless, a deeply touching one, and only in part by its submission of the head to a larger scheme: its color gradations, its careful balancing of the cool and warm tones, above all the luminousness of the face against the background, all play on our emotions.

Cézanne’s portraits are, of course, an integral part of his oeuvre. Whenever one studies his touch, his color use, or the integration of a head into a composition, one is attending to the formal devices by which all his paintings are judged and which justify his unparalleled position in the history of art. Nevertheless, his portraits offer each some particularity – such as the painter’s relation to his sitter, that we have looked at – that distinguishes them from landscapes and still lives. With the four portraits painted in the late 1880s of an adolescent model who wore a red waistcoat in each of them, Cézanne took advantage of the boy’s apparently spontaneous poses and portrayed him in relaxed, convincing positions that none of his other models had assumed (Le Garçon au gilet rouge, Fig. 8, FWN494-R656).

Of all of Cézanne’s figure studies, these four seem the most responsive to the sitter’s physiognomy—to his adolescent gangliness, his large hands, and his loose joints and relaxed spine—and are therefore among his freshest and least formulaic. But Cézanne also undertook a technical challenge, that of juxtaposing the red waiscoat, which is of a saturated vermilion and dominates the center of the paintings, against other colors, while avoiding the very likely clash. His solution in each painting – here the smallest of the four is presented – is to separate the red from the background by a white shirt, which is suffused and modeled with complementary greens. Where there are blues, as in the background and the boy’s kerchief, they are segregated from the red at points where they would have touched it, with other greens. The result is a magnificent portrait, based as much on a fresh, natural pose as on the painter’s profound engagement with an aesthetic question.

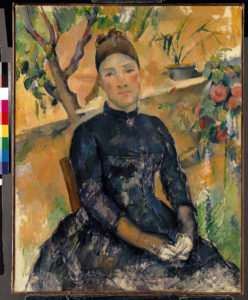

I had spoken of Cézanne’s ambivalent relation to his wife – which is confirmed in his biographies – and suggested that it was revealed in the the series of portraits that he painted of her over a span of twenty years. Having seen her as an impassive figure in Madame Cézanne à la jupe rayée, one is surprised to see her as a smiling, apparently happy woman in Madame Cézanne dans la serre (Fig. 9, FWN509-R703).

The painting is as bright in mood as it is light in illumination, having been painted in a conservatory—at the family residence, the Jas de Bouffan, in about 1891—and this explains the warm, flat light, the small tree, and the many plants located at odd points. What it was that pushed the painter and his wife to undertake so happy a pose in so cheerful a setting will never be known, but the technical ways by which the the painting was counterbalanced and the mood established are at least evident. The angle of the tree behind Madame Cézanne plays a crucial role. It parallels her head, the back of the chair, and by implication the small of her back. To see how important an element it is, we can obscure it with our finger; as we do so, we see her head quite differently, with it now it leaning more sharply to its right and back, and seeming coy; as we uncover it again, the head becomes oriented normally. Nevertheless the tree itself remains set at a distinct angle, and needs the counterweight of its other branches and the abstractly rendered top of the low wall to balance it. In all, the painting is happy and decorative, the figure of Madame Cézanne is simple and sculptural, and the whole is carefully balanced with little apparent difficulty on the painter’s part.

An altogether different mood prevails in the portrait of a young Danish painter who had come to visit Cézanne in 1899 and posed for the Portrait d’Alfred Hauge (Fig. 10 – FWN532-R835).

A somber painting, with an austerely posed figure, it is done in a new style, rougher and seemingly flatter, with emphatic outlines and large, detached patches of color. In Cézanne’s work the style is recent, and in portraits has been used only twice before, in Le Liseur (FWN512-R788, late 1890s) and Paysan assis (FWN523-R817).

As with his other styles, one must remember that they do not constitute a handwriting, a way of representing that characterizes a moment in time, but that they serve Cézanne when he needs them; several portraits of other sitters done in the final six years of his life, from 1900 to 1906, are also done in groups of touches, but they are gentler, more nuanced. Here, the rough facture is consistent with the stiff pose, as it is in Le Liseur – an equally rigid seated figure – and, to a lesser degree, in Paysan assis. It is also consistent with what we know about the sitter: in a photograph of him, a correct, carefully dressed, prim young man, and in his comments after leaving Cézanne, both admiring of the work and critical of the man.

Something of the sitter’s ambivalent attitude may have become apparent to the painter. Hauge later reported to a friend that in a fit of anger, Cézanne had slashed the painting with a knife (and that his son had it restored afterwords). It is not impossible that Cézanne was dissatisfied only with the work, but it seems more likely that the anger was displaced; in any case, the face is colorless, one is tempted to say bloodless, especially in contrast with the dark ground, and the touches are set down listlessly and rigidly, in one direction only. Surely the model’s skin was pale, but the choice of so dark a background seems to caricature it; and the mechanical touches are, in Cézanne, a sign of uninspired painting. Whether Cézanne’s approach was cautious from the beginning, or whether there were purely technical reasons for the painting’s awkwardness, we cannot know, nor can we exclude that with further application of paint, the touches might have softened. But is difficult to escape the impression that an emotional tone was here translated into paint from the start.

With Cézanne’s advancing age, his models became, quite naturally, progressively older. To some degree a painter identifies with the figures he paints, seeing some of their qualities in himself and projecting some of his own traits into them; it is a perfectly natural and unremarkable process. (Seeing the stiff pose of Alfred Hauge, Cézanne may have, as it were, stiffened up himself.) The identification can be encouraged by a similarity in age, irrespective of gender: an old woman with a rosary (La vielle au chapelet, FWN515-R808, 1895-96) can join the ranks of Cézanne’s male acquaintances, and his own aging gardener, in posing for him.

What is remarkable about Cézanne is that, whatever vigor remained in his old sitters, his own vigor – certainly as a painter — remained undimished; on the contrary, his last six years were years of restless inventiveness that would have been the envy of any young painter.

Cézanne painted his gardener about a dozen times, mostly in watercolor and at least three times in oil; the number is not clear, because some of the other late paintings of an old man – dark, brooding, abstract – may be either Vallier or someone else. Vallier himself appears in two of Cézanne’s most abstract and brilliantly colored outdoor portraits (FWN547-R950 and FWN546-R952) and appears as well in what may have been Cézanne’s last painting, Le jardinier Vallier (Fig. 11, FWN549-R954).

The painting is original in its conception — it shows the gardener by the first, horizontal light of the morning — and it is sustained in its vigorous handling. (One thinks of Caravaggio’s light, equally horizontal, but whose source is normally a low window.) Not only the light, but also the repeated, liquid, independent stabs at outlining the profile, are new to Cézanne’s oil portraits. Both effects are studied from watercolors; they are neither momentrary impulses nor tentative attempts to find the right outline, but serve instead to loosen the boundary between the smock and the dark wall, locating the sitter in space rather than on a flat plane. There is no sense of hesitation or ambivalence, as there was in the Hauge portrait; each patch of color carries the right weight, none intrudes. If identification with age drew Cézanne to older models, it did not constrain him in any way; on the contrary, it left him utterly free to advance his painting in what may have been, even to him, unpredictable directions.

If Cézanne’s sitters sat for him as still as apples, they ceased being apples as soon as he began to paint: their character, their station, their kinship tie – although not his principal object in painting them – were nevertheless revealed, and became an indissoluble part of the nexus of formal qualities that we call “a Cézanne portrait”.

Notes

[1] Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne. New York: Dover, 1984.

[2] See his preface to Joachim Gasquet’s Cézanne, London, Thames and Hudson, 1991, p. 9.

[3] See my discussion of the development of the parallel touch in my Cézanne: The Eye and the Mind (in French translation, Cézanne: La Sensation à l’oeuvre), Marseille: Crès, 2008, Chapter 3.

[4] Roger Fry, Cézanne, Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1989 (orig. published in 1927), p. 53.